5 Stages of Digestion

5 Stages of Digestion

Matt and Wade personally experienced this back in the 90s. They thought they were already in tip-top shape, but when they optimized their digestion and tried high doses of enzymes for 90 days, they gained muscle, lost fat, and experienced massive health improvements. Wade went on to compete in Mr. Universe and Mr. Olympia on a plant-based diet and 85 grams/day of protein, while his competitors needed 250 grams/day!

They also saw many clients who trained hard, ate well, and supplemented. But they didn’t achieve their full potential until they optimized their digestion, grew the right gut bacteria, and increased absorption.

You’re not what you eat but what you absorb. To optimize your health, it’s important to understand the five phases of digestion and how they impact your eventual absorption.

Phase 1: Anticipation

Food smells make you salivate, and your stomach grows because your brain is intimately involved with your digestion as much as your gut is. To optimize your digestion, you need to learn how to fully relax in “rest and digest” mode and be mentally engaged with your food.

Studies based on fMRI, which maps function to brain regions based on oxygen consumption, saw that parts of the brain lit up as subjects saw or smelled food. Our brains associate certain flavors with certain nutrition and caloric density of the food. Delicious and calorie-dense foods usually trigger a big dopamine release, which makes you feel rewarded.

The sight and sensation of food also trigger saliva, stomach acid, and digestive enzyme secretions2, 3. These processes happen through the “rest and digest” neurons called the vagus nerve. This is one of the most important neurons for health and gut-brain communications3.

Phase 2: Chewing/Mastication

Chewing serves many important functions.

First, it grinds foods into smaller pieces, making it easier for digestive enzymes to access the food later in the digestive process.

Second, it mixes the food with saliva so that you can taste it. Saliva lubricates and binds food into a bolus, so you can safely swallow it. The saliva also contains white blood cells, antibodies, and lysozyme (a bacteria-digesting enzyme), which kills pathogens that could be in your food.

Third, chewing stimulates stomach acid and digestive enzyme secretions throughout the digestive tract6. Typically saliva only serves as a lubricant and contains minimal digestive enzymes. But once chewing commences, the salivary glands release digestive enzymes, such as salivary amylase (starch-digesting) and lipase (fat-digesting). In sham feeding studies, chewing food (and spitting them out) was enough to trigger the pancreas to release 50% of total digestive enzymes it would secrete in a meal7.

Fourth, chewing stimulates the vagus nerve, which not only reduces inflammation throughout your body but also helps you relax. So that further stages of digestive function can function optimally8.

Therefore, taking the time to chew your food properly is important. Rushing your meals and not chewing thoroughly can result in discomfort, indigestion, and even acid reflux.

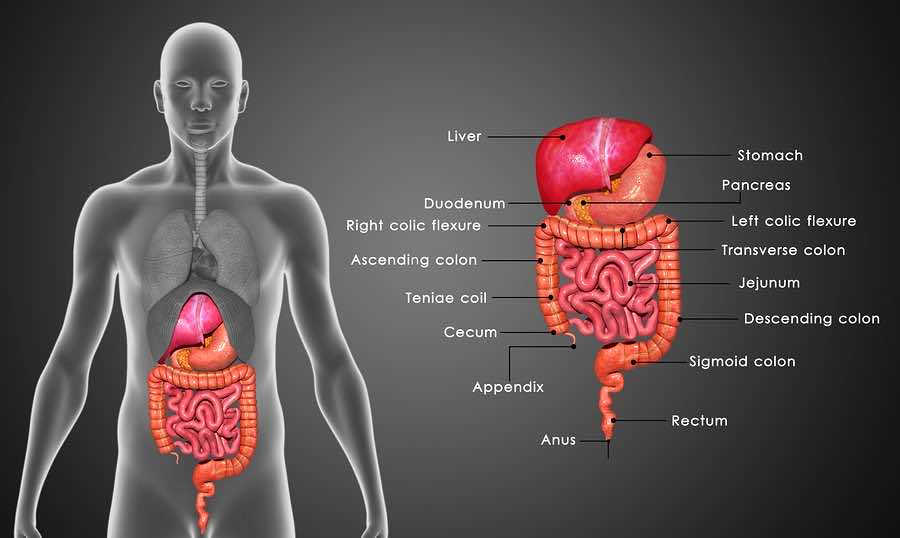

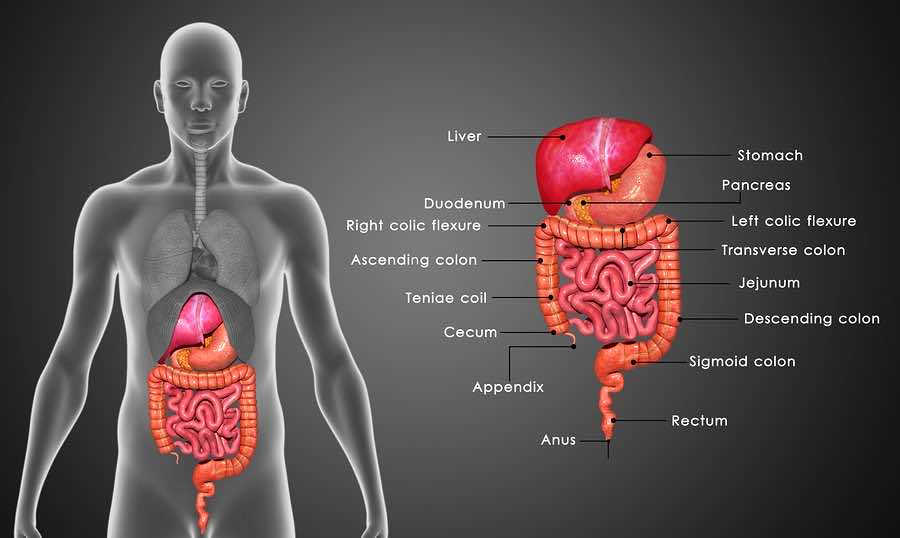

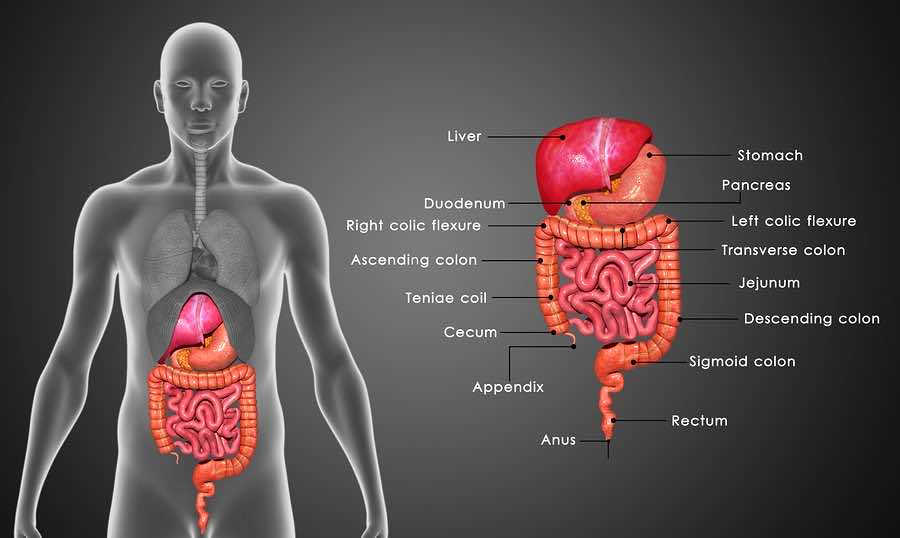

Phase 3: Stomach

The stomach is where most of the food breakdown starts. It secretes stomach acid and digestive enzymes and moves to mix food with the acid and enzymes.

Stomach acid plays many important roles, including:

- Signaling the valve between the esophagus and stomach to close, preventing acid reflux

- Preventing infections by killing most microorganisms and parasites

- Activating pepsin, a key protein-digesting enzyme in the stomach

- Loosening up the molecular structure of the foods, allowing easier access to enzymes

- Freeing up minerals such as calcium, magnesium, and iron into absorbable forms

- Freeing up vitamin B12 to mix with intrinsic factors to be absorbed in the large intestine

- When the food travels from the stomach to the small intestine, the bolus’s acidity activates further digestion stages.

Low stomach acid will create an unhealthy ripple effect throughout the body, including reduced appetite, increased risk of gut infections, and deficiencies in minerals, protein, and vitamin B12. These tend to happen in the elderly, those under stress, and those with weak vagus nerves. Small intestine bacterial overgrowth may also occur due to reduced peristalsis, resulting in gas, bloating, and potentially diarrhea or constipation.

Fortunately, taking a betaine HCL supplement, such as HCL Breakthrough, may be one of the easiest and most affordable tips to improve your digestive function.

Phase 4: Small intestine

Once the food reaches the small intestine, your anticipation triggers 50% of the digestive juices. The acidity of the food bolus will trigger the remainder of it. The small intestine is where most of the digestion occurs, including the secretion of:

- Bile helps emulsify fats into smaller droplets, allowing lipase to digest the fat molecules.

- Pancreatic amylase to digest starches.

- Protein-digesting pro-enzymes are then activated in the small intestines to digest proteins.

- Sugar-digesting enzymes, such as sucrase, maltase, and lactase, digest sucrose (table sugar), maltose (sugars with two glucose molecules), and lactose (milk sugar), respectively.

Peristalsis moves the food bolus along as the food gets digested and absorbed. Nutrient absorption also depends on the integrity of the mucosal barrier, the single-cell lining of the gut, and villi structure, finger-like structures that maximize the absorptive surface. The mucosal barrier and villi structure are often compromised in untreated celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, gut infections, and other sources of gut inflammation 10-12.

Incomplete digestion can result in partially digested peptides, carbohydrates, and fats. The large intestine’s gut bacteria may ferment peptides and carbohydrates, whereas the fat tends to be excreted as stool fat. Protein fermentation may create metabolites such as hydrogen sulfides, ammonia, and phenol, which smell bad.

Therefore, one of the most important steps to improve poor inflammatory response is ensuring optimal protein digestion. Most people with chronic inflammation also have reduced stomach acid and enzymes, so supplementation is often beneficial. Proteases are the most expensive ingredient of any digestive enzyme products, so many manufacturers cut corners on them. MassZymes has the highest dose of active protease on the market, which can help ensure you absorb all the nutrients your body needs and reduce inflammation from incomplete digestion.

Phase 5: Large intestine and elimination

Here, most of the digestive functions are complete. The large intestine absorbs most of the water, electrolytes, and vitamin B12. In addition, this is where your gut microorganisms take the stage.

To learn more about gut bacteria and digestive health, and how to optimize your gut bacteria with probiotics supplements, check out this article.

References:

- Dagher, A. Functional brain imaging of appetite. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism vol. 23 250–260 (2012).

- Katschinski, M. Nutritional implications of cephalic phase gastrointestinal responses. in Appetite vol. 34 189–196 (Academic Press, 2000).

- Tiwari, M. Science behind human saliva. Journal of Natural Science, Biology and Medicine vol. 2 53–58 (2011).

- Fábián, T. K., Hermann, P., Beck, A., Fejérdy, P. & Fábián, G. Salivary defense proteins: Their network and role in innate and acquired oral immunity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences vol. 13 4295–4320 (2012).

- Lashley, K. S. Reflex secretion of the human parotid gland. J. Exp. Psychol. 1, 461–493 (1916).

- Anagnostides, A., Chadwick, V. S., Selden, A. C. & Maton, P. N. Sham feeding and pancreatic secretion. Evidence for direct vagal stimulation of enzyme output. Gastroenterology 87, 109–14 (1984).

- By gum, it might be good for you – Harvard Health. (2006) //www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter_article/By_gum_it_might_be_good_for_you Date accessed: 03/27/2020.

- Keller, J. & Layer, P. The pathophysiology of malabsorption. Viszeralmedizin: Gastrointestinal Medicine and Surgery vol. 30 150–154 (2014).

- Blander, J. M. Death in the intestinal epithelium—basic biology and implications for inflammatory bowel disease. FEBS Journal vol. 283 2720–2730 (2016).

- Evenepoel, P. et al. Evidence for impaired assimilation and increased colonic protein fermentation, related to gastric acid suppression therapy. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 12, 1011–1019 (1998).

- Brooke-Taylor, S., Dwyer, K., Woodford, K. & Kost, N. Systematic Review of the Gastrointestinal Effects of A1 Compared with A2 β-Casein. Adv. Nutr. An Int. Rev. J. 8, 739–748 (2017).