Nutrition for Optimal Connective Tissue Health: Joints, Tendons, Ligaments, and Bones

Nutrition for Optimal Connective Tissue Health: Joints, Tendons, Ligaments, and Bones

It’s also common to accept the fate of a long, strenuous recovery process. But what if you could strengthen your tissues against these injuries and provide what your body needs for a speedy recovery?

As a physical therapist, I treat both acute and chronic injuries daily. Understandably, you want to recover as fast as possible, but healing and recovering is a process. There are no quick fixes, but there are techniques you can use to help support this process.

Doctors and therapists often neglect nutrition as a key factor in the healing and recovery process. You may have heard about how proteins help build muscles. Whereas, the majority of traumatic and overuse injuries involve connective tissues that work with the muscles, such as bones, joints, tendons, ligaments, and fascia.

Not only can proper nutrition accelerate healing, but it can also improve the tensile strength of connective tissue and prevent future injuries.

In this article, you will learn what connective tissue is, why it’s important, and how to support the health of your connective tissue through nutrition.

What is Connective Tissue and Why Is It Important?

There are 4 main types of tissue in the human body: connective, muscular, nervous, and epithelial tissue. Connective tissue protects and supports everything in the body.

Connective tissue subtypes include

- bones

- joints and cartilage

- tendons

- ligaments

- fascia

- skin

- fat

- blood, and more

Because connective tissue provides structure to your body, damage to these tissues can compromise your entire body, including the organs. The main structural components of connective tissues include collagen and elastin.

What are Collagen and Elastin?

Two main proteins provide structure to your connective tissue: collagen and elastin.

- Collagen is the protein that provides strength and stability. Imagine collagen as the steel-rod beams of a high-rise building.

- Elastin is the protein that provides flexibility and allows tissue to be stretched and recoiled, like a rubber band does.

Your connective tissues need a balance of both protein types to have tensile strength, meaning able to stretch but not snap. Connective tissue subtypes have different percentages of each protein, depending on their function. For example, bones contain more collagen than elastin because they require greater stability. Whereas, skin has more elastin than bones because skin needs to be stretchier.

Being familiar with these proteins is important because your body needs these building blocks in order to keep your connective tissues strong and healthy. How do you do that? First, by putting force on your connective tissues so they get the signals to be stronger. Second, by repairing them. Growth in any aspect of life occurs when something is first stressed, triggering the body to grow and adapt to be able to withstand the stress.

With connective tissue, exercise (especially lifting weights) first stresses the tissues. Then, your tissues repair when your body obtains the necessary nutrients and rest.

If you stress the tissue but never provide the necessities for repair, recovery is more difficult or may never be fully met. This sets your body up for chronic injuries or more damage during accidents. A minor incident may inflict more devastating consequences.

A healthy body is a resilient body– able to prepare, load, and recover. In your healthy body, a major trauma may be less damaging because you have given it the nutrition and rest necessary to be resilient.

Before we dive into the science behind nutrition, let’s take a quick look into 5 connective tissue structures that are important to protect. Consider these when looking to improve your function or mobility, prevent injury, or accelerate healing.

5 Connective Tissue Structures Commonly Hurt, Injured, or Degenerated

- Bones

Common injuries to bones include acute and stress fractures.

Acute fractures occur with a traumatic incident, such as falling. Young children and the elderly are at greater risk of acute fractures because of their bone density. Kids have immature bones that are not fully ossified. People lose bone density as they age, which may lead to osteopenia or osteoporosis, and an increased risk of fracture. Severe nutrient deficiencies and some hormonal issues can also contribute to poor bone health.

Stress fractures are overuse injuries when a repetitive activity leads to wear on a specific, weakened portion of bone. For example, a runner may get a foot stress fracture when increasing their weekly running distance from 10 miles to 30 miles. Stress fractures occur over time when the body is not prepared for an activity load.

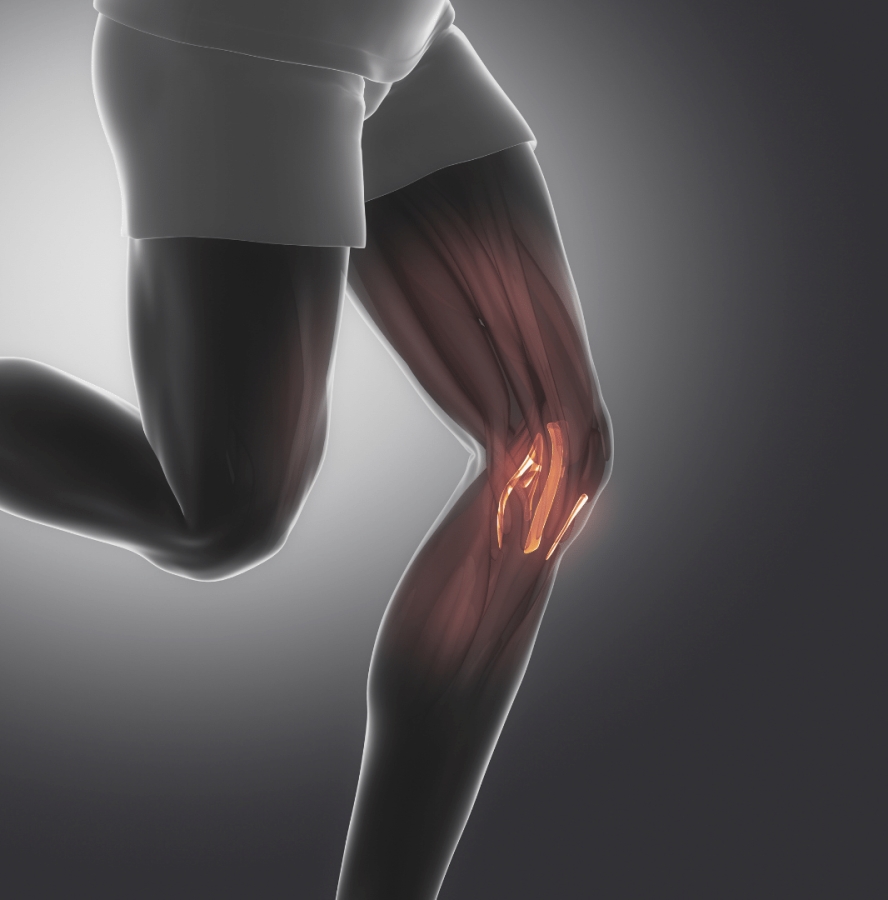

- Joints

Joints are where the surface of 2 or more bones meet. Joints are surrounded by different types of protective connective tissue which hold the bones together and prevent “grinding” of the bones. Mainly, cartilage, the strong and flexible connective tissue, covers the ends of your bones where they meet in your joints.

Osteoarthritis happens when the knee joint space narrows as a result of chronic wear on its protective structures, especially the cartilage or meniscus.

Keeping the surrounding structures of joints healthy ensures better alignment and stability of the joint spaces. These protective structures include labrums, discs, ligaments, and fat pads. If you have an injury to one of these, maximizing your recovery may help reduce future joint dysfunction.

- Tendons

Tendons are the structures that connect muscles to bones. While muscles are contractile tissue, meaning they actively contract (shorten) and move, tendons are non-contractile. Tendons are passive structures that serve as a link for a muscle to move a bone.

Imagine a kid pulling a sled. The kid is muscle (actively moving), the rope is tendon (passively connecting), and the sled is bone (object receiving the motion). If the rope (tendon) is frayed, the kid will move the sled more cautiously to prevent the rope from snapping.

Common injuries to tendons include tendinopathies and tendon tears/rupture.

Tendinopathy is an overuse injury. A common example is Achilles tendinitis, which occurs after overdoing an activity for a few days or weeks. The tendon becomes inflamed and painful when walking or running. If the Achilles tendinitis never fully recovers, this can progress to chronic tendinosis.

A degenerated Achilles tendon is at higher risk of tear or rupture. Small tears can occur gradually, or larger ones can occur suddenly when jumping or falling. A rupture is a full tear of the tendon.

- Ligaments

Ligaments are the structures that connect bones to bones. They hold bones together and joints in place. Ligaments receive less blood supply than muscles or tendons, and therefore are slower to heal. Like tendons, ligaments are non-contractile and are at risk of being overstretched.

When ligaments are chronically overstretched, they become lax, or loose. Increased laxity can cause increased wear on the ligaments themselves and on the joints they are supposed to support. This increased laxity allows for too much movement at joints and can lead to joint instability. When joints are unstable, they wear on all the other connective structures previously discussed.

For example, if a basketball player sprains his ankle over and over, the ligaments get progressively lax. The ankle joint moves too much and will wear out the cartilage structures within the joint, leading to the need for potential surgical repair in the future.

Common injuries to ligaments are sprains and ruptures. Sprains are acute injuries, such as suddenly twisting an ankle while hiking on uneven terrain. There are 3 grades of sprains (mild, moderate, and severe), with severe being a complete tear or a rupture. Spraining the same ligament over and over can put that ligament at risk for increased laxity and increased risk of rupturing in the future.

- Fascia

Fascia is the connective tissue that connects every structure in the body together. Its fibers form a casing like a bodysuit, which holds skin, muscles, nerves, organs, and vessels in their proper place.

The significance of fascia is underappreciated and misunderstood. It’s not just a protective and connective sheath. Rather, it is an intricate, three-dimensional web of highly-innervated tissue, designed to allow the human body to perform fascinating physical feats. Fascia allows structure in a dynamic system.

It’s estimated that water makes up 45-75% of the human body. Without fascia to hold everything together, your body would be a blob of tissue.

Fascia can get tight as a protective response, overstretched, or scarred down. For example, plantar fasciitis is an inflammation of the fascia on the bottom of the foot. Microtears occur in the fascia in response to overuse.

Having hydrated and strong fascia is important to maintain good body structure, alignment, and movement mechanics. So, how can you support the health of your fascia and connective tissue? By providing the body with the right building blocks from good nutrition.

How Does Nutrition Support the Health of Your Connective Tissue?

Good food supplies the body with the nutrients necessary to repair damaged tissue and build healthy tissue. Poor quality food leads to poor quality of health, including your connective tissue health.

In First World countries, we have an overabundance of “food stuff”. This “food stuff” is hyper-palatable and lacks quality. It is a false version of real food and lacks many nutrients needed to sustain a healthy, resilient body. The Standard American Diet often lacks amino acids and micronutrients that feed your connective tissue, for example.

Real food contains all the necessary nutrients needed to help the body adapt, repair, and grow. Protein is the macronutrient that builds and signals. Protein molecules are the building blocks for everything in the body, including muscle mass and connective tissue. They also signal where and how to build.

When connective tissue gets worn, enzymes signal the body to repair itself with other structural proteins. As previously discussed, the main structural protein in this repair is…you guessed it – collagen!

Amino acids are the smaller building blocks of protein. These can be ingested via food proteins or amino acid supplements.

Other important nutrients needed to keep all proteins functioning efficiently include vitamins, minerals, and fatty acids. These are discussed in further detail below.

Nutrients Essential to Prevent and Repair Injury

Every human requires basic nutrients to maintain their health. In times of stress, injury, or surgery, the nutrition requirements increase to repair damaged tissue.

- Vitamins

- Vitamin C is a required nutrient to build collagen. Combined with the intake of dietary collagen, vitamin C increases the production of collagen in the body and improves tendon and ligament repair.

Foods high in vitamin C include many colored fruits and vegetables, such as citrus, strawberries, bell peppers, and broccoli.

- Vitamin D is a hormone that controls the integration of calcium into bone and affects bone health. When vitamin D levels are low, the body pulls calcium from the bones into the blood. Low levels of vitamin D are correlated with decreased bone density.

One study showed that supplementing 700-800 IU of vitamin D per day reduced the risk of nonvertebral fractures in the elderly.

Vitamin D is best obtained through sunlight exposure. UVB rays from the sun interact with the skin to produce vitamin D. Foods naturally containing vitamin D include fish, liver, and mushrooms.

- Vitamin K affects bone strength as well. While vitamin D helps your gut absorb calcium, vitamin K helps bring calcium to your bones.

Vitamin K1 is found in dark leafy greens. Vitamin K2 is found in chicken, liver, eggs, butter, cheese, and natto. K2 is more readily taken up and used effectively in the body than K1.

- Minerals

- Calcium is deposited to give bones their iconic hard structure. Calcium is important to obtain through diet to maintain good bone density and strength. [6] Foods rich in calcium include fish, dairy, and dark leafy greens.

- Magnesium improves bone density and is essential for collagen production throughout your body. Magnesium is found in fish, nuts, seeds, avocados, dark leafy greens, and dark chocolate.

- Trace elements like zinc and copper contribute to regulating bone density[6] and collagen synthesis. Zinc and copper are found in oysters, liver, red meat, chicken, fish, dairy, nuts, and seeds.

- Amino acids

- Glycine is the most abundant amino acid to make up collagen and elastin. Many people don’t eat enough glycine if they focus their diet on muscle meats and not enough organ meats or bone broth. Dietary glycine promotes a balanced inflammatory response and supports tendon and joint health.

- Glutamine is a precursor to proline, the second most abundant amino acid in collagen and elastin. Glutamine can support healthy tissue healing and collagen synthesis and improves the uptake of vitamin C.

- Arginine is also a precursor to proline. Supplementing with arginine can improve wound healing via increased collagen production.

- Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate

Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate are compounds that makeup cartilage. Taken as a nutritional supplement, glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate improve joint health and may preserve joint tissues.

- Omega-3 fatty acids

Omega-3 fatty acids are known for their inflammation-balancing effects throughout the body. When omega-3 fatty acids are combined with supplements such as glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, they have a protective effect on the cartilage and may relieve joint discomfort.

Foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids include fish, fish oils, walnuts, and flax seeds.

- Systemic enzymes

Systemic enzymes are proteolytic enzymes taken without food. They include bromelain, papain, trypsin, and chymotrypsin. These are used to relieve discomfort, support the removal of healing debris, and may improve tissue healing.

Best Foods to Support Connective Tissue Health

When looking to support your connective tissue health, the most important structure to consider is collagen. Tough cuts of meat, organ meats, and bone broth are the foods most abundant in collagen. Unfortunately, since most people focus on muscle meats, especially leaner and more tender cuts, they tend not to get enough collagen, glycine, and proline. While these are non-essential amino acids, consuming more tends to provide health benefits.

Consider adding these foods to your diet, ideally from grass-fed and humanely-raised animals and healthy sources of seafood. Also, eating a variety of fruits and vegetables provides anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. They also contain vitamins, minerals, fibers, and healthy carbohydrates.

Collagen peptides (also called collagen supplements) are collagen broken down into smaller snippets using acid, enzymes, or heat.

Aside from providing key building blocks for collagen and elastin, collagen peptides also provide cellular signals in your body that stimulate connective tissues to grow stronger and self-repair. They may also promote a balanced inflammatory response in joints, bones, and tendons., and support many anti-aging processes in your body. So, collagen supplements like Mushroom Breakthrough should be a staple if you want to support your joints, tendons, ligaments, and bone health along with exercise or physical therapy (when applicable).

Conclusion

Getting your nutrition right and getting consistent exercise with resistance training are keys to maintaining optimal connective tissue health. If you’re recovering from an injury, consider working with a physical therapist or a sports medicine physician to heal and strengthen your tissues. At the same time, remember to support your body nutritionally by providing it with the building blocks, vitamins, and minerals that it needs.

References

- Papadopoulou SK. Rehabilitation nutrition for injury recovery of athletes: The role of macronutrient intake. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):2449. doi:10.3390/nu12082449

- Kumka M, Bonar J. Fascia: a morphological description and classification system based on a literature review. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association. 2012;56(3):179-191.

- Kamrani P, Marston G, Jan A. Anatomy, Connective Tissue. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Zügel M, Maganaris CN, Wilke J, et al. Fascial tissue research in sports medicine: from molecules to tissue adaptation, injury and diagnostics: consensus statement. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(23):1497-1497. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-099308

- Stock J. Wolff’s law (bone functional adaptation). The International Encyclopedia of Biological Anthropology. 2017;1.

- Price CT, Langford JR, Liporace FA. Essential nutrients for bone health and a review of their availability in the average north American diet. Open Orthop J. 2012;6(1):143-149. doi:10.2174/1874325001206010143

- Ohashi Y, Sakai K, Hase H, Joki N. Dry weight targeting: The art and science of conventional hemodialysis. Semin Dial. 2018;31(6):551-556. doi:10.1111/sdi.12721

- Turnagöl HH, Koşar ŞN, Güzel Y, Aktitiz S, Atakan MM. Nutritional considerations for injury prevention and recovery in combat sports. Nutrients. 2021;14(1):53. doi:10.3390/nu14010053

- Tack C, Shorthouse F, Kass L. The physiological mechanisms of effect of vitamins and amino acids on tendon and muscle healing: A systematic review. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2018;28(3):294-311. doi:10.1123/ijsnem.2017-0267

- Holick MF. The role of vitamin D for bone health and fracture prevention. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2006;4(3):96-102. doi:10.1007/s11914-996-0028-z

- Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC, Wong JB, Giovannucci E, Dietrich T, Dawson-Hughes B. Fracture prevention with vitamin D supplementation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;293(18):2257-2264. doi:10.1001/jama.293.18.2257

- Halder M, Petsophonsakul P, Akbulut AC, et al. Vitamin K: Double bonds beyond coagulation insights into differences between vitamin K1 and K2 in health and disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(4):896. doi:10.3390/ijms20040896

- Kavalukas SL, Barbul A. Nutrition and wound healing: an update. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127 Suppl 1:38S-43S. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e318201256c

- Albaugh VL, Mukherjee K, Barbul A. Proline precursors and collagen synthesis: Biochemical challenges of nutrient supplementation and wound healing. J Nutr. Published online 2017:jn256404. doi:10.3945/jn.117.256404

- Kjaer M, Frederiksen AKS, Nissen NI, et al. Multinutrient supplementation increases collagen synthesis during early wound repair in a randomized controlled trial in patients with inguinal hernia. J Nutr. 2020;150(4):792-799. doi:10.1093/jn/nxz324

- Deal CL, Moskowitz RW. Nutraceuticals as therapeutic agents in osteoarthritis. The role of glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and collagen hydrolysate. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1999;25(2):379-395. doi:10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70074-0

- Paradis ME, Couture P, Gigleux I, Marin J, Vohl MC, Lamarche B. Impact of systemic enzyme supplementation on low-grade inflammation in humans. PharmaNutrition. 2015;3(3):83-88. doi:10.1016/j.phanu.2015.04.004

- Khatri M, Naughton RJ, Clifford T, Harper LD, Corr L. The effects of collagen peptide supplementation on body composition, collagen synthesis, and recovery from joint injury and exercise: a systematic review. Amino Acids. 2021;53(10):1493-1506. doi:10.1007/s00726-021-03072-x

- Honvo G, Lengelé L, Charles A, Reginster JY, Bruyère O. Role of collagen derivatives in osteoarthritis and cartilage repair: A systematic scoping review with evidence mapping. Rheumatol Ther. 2020;7(4):703-740. doi:10.1007/s40744-020-00240-5