Problems with RDA for protein intake and the new evidence-based recommendations

Protein is the most important macronutrient, but one of the myths is that the Food and Nutrition Board’s Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) of 0.8 g/kg/day is the ideal intake.

Why RDA Is Often Confused With Optimal Intake

Growing up, we learned to read the labels on our foods to determine how healthy something is or if we get a particular vitamin from it. You can see the grams or milligrams and the percentage of your daily intake that eating a serving size of that food will make up. Seeing 100%, or even more, allows us to assume we are getting enough of something.

RDA is only enough to prevent severe deficiencies in healthy and nutrient-sufficient people. Therefore RDA is far from what’s optimal for everyone. Rather than being referred to as a recommended daily intake, it should be considered the minimum intake.

At BIOptimizers, we aim to help people optimize their BiOptimization triangle - that means aesthetics, performance, and health. Therefore, the RDA level is far from sufficient if you want to look and feel great, think clearly, and perform your best, especially well into old age.

How The Protein RDA Was Determined And Why It’s Outdated

Nitrogen Balance Studies

If RDA isn’t optimal, why did they come up with it in the first place? The Food and Nutrition Board determined the protein RDA based on nitrogen balance.

First of all, why determine protein requirements based on nitrogen? Roughly every 6.5 grams of protein you eat contains 1 gram of nitrogen. It leaves the body through your urine, feces, and skin. Because protein is the only energy-producing nutrient that contains nitrogen, nitrogen can measure protein.

We can determine nitrogen balance by comparing the amount of nitrogen intake and nitrogen output. There are three possible outcomes:

- Nitrogen equilibrium: nitrogen in = nitrogen out. You are neither gaining nor losing protein.

- Positive nitrogen balance: nitrogen in > nitrogen out. You are gaining lean tissue and muscle.

- Negative nitrogen balance: nitrogen in < nitrogen out. You are losing body protein.

The protein RDA is based on the amount of protein it takes to achieve nitrogen equilibrium. Additionally, nitrogen balance tends to overestimate nitrogen intake and underestimate nitrogen output.

By focusing only on protein intake and urinary nitrogen output, nitrogen balance also fails to consider all sources of nitrogen output, such as hair and nails, saliva, and breath. It also fails to take into account other nitrogen compounds in foods, such as nucleotides.

Who were the guidelines made for? This is part of the problem with protein RDA. The recommendations were for healthy, inactive young adults. That means they don’t apply to everyone else. Obviously, your optimal protein requirements depend on your age, lifestyle, and health status.

How It Should Be Measured

Where RDA falls short, the indicator amino acid oxidation (IAAO) method steps in. Amino acids are at the crux of this method. Indispensable, or the nine essential amino acids, are vital throughout your body. They are necessary for tissue repair, nutrient absorption, and protein synthesis, and you can only get them through your diet. They include:

- Histidine

- Isoleucine

- Leucine

- Lysine

- Methionine

- Phenylalanine

- Threonine

- Tryptophan

- Valine

The idea behind the IAAO method is that when one of these indispensable amino acids is too low for protein synthesis, none of the other amino acids can be used. The excess of all the rest will be oxidized or broken down as energy.

When the amino acids are used as energy, their carbons are released as carbon dioxide through your breath. The limiting amino acid is the one amino acid that is so low that it limits protein synthesis from continuing.

Let me give you an example of how this method works. Let’s say you determine that phenylalanine is the indicator amino acid or the one you are tracking. Typically, the indicator phenylalanine would be trackable through radioactive carbon atoms in the amino acid.

If your protein intake is so low that you don’t have enough of all of the indispensable amino acids, the amount of carbon dioxide produced by phenylalanine oxidation increases. An increase in this oxidation means you are not meeting your protein requirement.

On the other hand, if you begin eating protein, the radioactive carbon dioxide produced by phenylalanine oxidation will decrease until your protein intake meets your body’s protein requirement.

If you eat more protein than your body needs, the radioactive carbon dioxide will remain constant. Scientists refer to this as your break-point, and that is your protein requirement.

By directly measuring your protein usage and amino acid breakdowns, the IAAO method is a much more accurate way to estimate protein needs.

Optimal Protein Intake Varies Based On Different Circumstances

Your optimal protein intake depends on many factors, including:

- Weight

- Activity level

- Gender

- And goals

Remember that everybody is different. These are starting points for your protein intake based on IAAO and other clinical studies, and you should experiment with the best amount.

Active People

If you are an active adult at a healthy weight, the amount of protein you should consume depends on your weight goals.

Maintain Your Current Weight

If you are an average exercising adult, you should aim for 1.4–2.0 g/kg (0.64–0.91 g/lb) of protein per day to maintain your current weight.

Muscle Building

Building muscle requires additional protein, but more protein does not mean more muscle gain. The ideal consumption range for most is 1.6-2.4 g/kg (0.73-1.0 g/lb) of protein per day. More protein than this does not make significant changes in body composition.

Eating protein at the higher end of the ideal range (around 2.4 g/kg or 1.0 g/lb) can help minimize fat gain when on a caloric surplus.

Weight Loss

When trying to lose weight or body fat, it’s important to preserve your lean body mass. Even if you restrict calories, you should maintain your protein intake from 1.6–2.4 g/kg (0.73-1.0 g/lb). The more you limit your calories, the higher your protein intake should be to avoid muscle loss.

Also, a high-protein diet makes it easier to lose weight because:

- Protein is more satiating and keeps you full longer.

- Protein tends to have minimal impact on your blood sugar.

- Your body needs more calories to digest, assimilate, and burn proteins than carbohydrates and fats.

Men And Women

Gender does make a difference when it comes to optimal protein intake. When it comes to training, men need to consume more protein than women. On training days, men should consume 2.1–2.7 g/kg (.95-1.22 g/lb), while women should consume 1.4–1.7 g/kg (.64-.77 g/lb).

For women, it also matters where you are in your menstrual cycle. Protein oxidation increases during your luteal phase (after ovulation and before the start of your period). Optimal protein intake for women during this time is around 1.6 g/kg (.73 g/lb) per day.

Pregnancy And Lactation

Growing a baby requires extra protein. If you are pregnant, ensuring that you are getting adequate protein intake is critical for supporting the health of both you and your baby. Protein supplementation during pregnancy reduces the risk of:

- Stillbirth

- Low gestational weight

- Low birth weight

The amount of protein you need to consume depends on how many weeks you are pregnant. Suggested requirements are:

- Early pregnancy (11-20 weeks): 1.22 g/kg (.55 g/lb)

- Late pregnancy (30-38 weeks): 1.52 g/kg (.69 g/lb)

Protein needs while breastfeeding are similar to those during late pregnancy. The recommendation is to consume at least 1.5 g/kg (.68 g/lb).

Aging Population

With age comes an additional risk of muscle loss, which can start as early as in your 30s. To the point that it impairs your physical function, it is called sarcopenia. Sarcopenia is also the leading cause of frailty. Symptoms of frailty include:

- Unintentional weight loss

- Muscle loss and weakness

- Fatigue

- Slow walking speed

- Low physical activity levels

Living with frailty puts you at a higher risk of:

- Needing to go to a nursing home for additional care

- Falls

- Fractures

- Hospitalization

Good news: frailty can be an avoidable part of aging. It can ensure that your protein intake and resistance training stimulates muscle protein synthesis.

Older adults should aim for 1.2–1.5 g/kg (.54-.68 g/lb) of protein daily. Increasing your protein intake can improve your body composition by stimulating the mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, even in older adults.

Healthy (higher) protein intake in the elderly can preserve bone mass and significantly reduce the risk of hip fracture, according to a systematic review of 13 studies. Hip fractures affect 1/3 older adults and tend to lead to slow and painful deaths. This injury triples the risk of complications, that eventually lead to death, for up to 10 years.

Children

Children grow and develop rapidly and need to consume adequate protein to support their bodies. Children ages 6-11 should aim for 1.5 g/kg (.68 g/lb) of protein daily. Similar to adults, a more active lifestyle, such as sports, requires an additional increase in protein consumption.

Protein Quality And Complete vs. Incomplete Protein

So you want to increase your protein intake? Does all protein count the same? No. Remember that amino acids are the building blocks of protein, and there are nine indispensable (essential) ones. Without a sufficient amount of one of them, protein synthesis stops.

Complete proteins contain all nine indispensable amino acids. Incomplete proteins are missing one of the amino acids or do not contain enough of at least one to support protein synthesis. Many plant-based proteins also have lysine as a limiting amino acid, thereby halting protein synthesis. This is especially true for grains such as rice, wheat, and nuts and seeds.

Sources Of Complete Proteins

Some of the best sources of complete proteins are animal products, including:

- Meat

- Poultry

- Fish

- Eggs

- Dairy (including whey protein)

There are also a few sources of plant-based complete proteins, such as:

- Quinoa

- Buckwheat

- Hemp seed protein

- Chia seed proteins

- Potatoes

- Soy products such as tofu and tempeh

- Seitan (wheat protein)

- Spirulina

- Mycoprotein (AKA Quorn, made from naturally occurring fungus)

Protein Quality And Plant-Based Diets

So, what if you are vegan or vegetarian? It must be harder to get enough protein, right? It takes a little extra thought and planning, but it’s doable. Think of it as creating the perfect protein package. If you cannot eat enough complete proteins, you should focus on eating quality proteins that complement each other to give you all nine indispensable amino acids daily.

Protein Quality

Plant-based proteins tend to be lower-quality proteins than animal-based proteins. Two factors determine the quality of a protein: digestibility and amino acid profile. You already know why getting all nine indispensable amino acids is essential, so let’s focus on digestibility.

If your body cannot break down and absorb the protein you eat, your body can’t use it. Animal proteins are digestible at around 90%, whereas plants hover at about 60-80%.

Anti-nutrients like trypsin inhibitors, phytates, and tannins in plants contribute to the indigestibility of plant proteins. Cooking can reduce the effects of anti-nutrients, but does not eliminate them. The best sources of digestible plant proteins are plant-based protein powders, such as soy protein isolate, as the processing removes most of the anti-nutrients.

However, soy products may also contain phytoestrogens and goitrogens, which can cause hormone imbalances, especially in men. Therefore, other plant-based complete protein powders, such as Protein Breakthrough, are safer to consume on a regular basis.

Creating Your Complete Protein Package

One of the easiest ways to get enough protein from a plant-based diet is to eat more. Another more intelligent way is to combine complementary proteins to create a diet package with a complete amino acid profile. Pairing grains with legumes or nuts and seeds with legumes are a great option. Some examples include:

- Nuts or seeds (butter) with whole grain bread

- Beans with whole grains

- Beans with nuts or seeds

Additionally, most plant proteins are low in leucine, so adding a plant-based leucine supplement to your diet will help balance any deficiency. Leucine is also a key activator of mTOR pathway, so adding leucine can enhance muscle-building efforts.

Adding Plant-Based Digestive Enzymes

Supplementing with plant-based digestive enzymes high in proteases, such as MassZymes, can help overcome low protein digestibility due to protease inhibitors. These enzymes can also ensure that proteins that are hard to digest, such as lectins and glutens, are broken down into usable amino acids rather than left to irritate the gut.

Many people find it hard enough to get enough protein on an omnivore diet, so it can be even more challenging on a plant-based diet. Plant-based digestive enzymes can help make sure that every gram of protein counts.

Downsides Of A High Protein Diet

While getting enough protein is essential, getting too much protein can adversely affect your health.

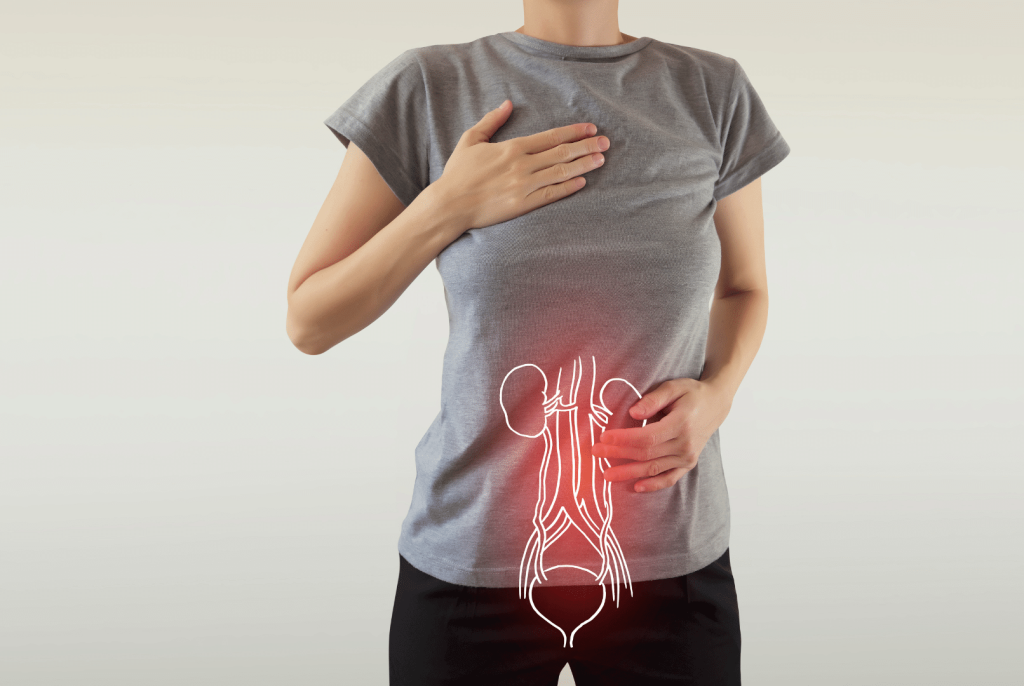

Kidney Issues

Avoid a high-protein diet if you have a pre-existing kidney problem. Overeating protein increases the rate at which your kidneys filter your blood, called hyperfiltration. This increase causes the kidneys to produce excessive amounts of protein in your urine. Hyperfiltration can indicate other diseases such as chronic kidney disease, pre-diabetes, or pre-hypertension.

Nutritionists used to think that high protein diets can damage kidneys. However, recent studies show that hyperfiltration due to a high-protein diet is only an issue if you have pre-existing kidney problems.

Microbiota Impact

Gut microbes play an essential role in the digestion, absorption, and metabolism of protein in your gastrointestinal tract. Protein is metabolized in the small intestine, releasing amino acids for protein synthesis.

When you have a lot of undigested protein and leftover amino acids, your gut microbes can ferment them. Amino acid fermentation can create harmful metabolites such as quinolinic acid, ammonia, and hydrogen sulfide.

High levels of harmful metabolites increase your risk of colon disease. As discussed above, one way to counteract these effects on your gut is to prioritize digestible proteins and maximize your protein digestion with digestive enzymes and HCL.

Charred Or Processed Meat Can Be Toxic And May Increase Oxidative Stress

The type of meat and how it’s cooked can make a difference in how healthy it is.

Charred Meat

There’s nothing quite like a perfectly cooked steak or grilled fish flavor, but you may want to save it for special occasions. Cooking meat at high temperatures, such as pan frying or grilling, produces chemicals called heterocyclic amines (HCAs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). These chemicals can cause mutations in your DNA and increase your risk of cancer.

The International Agency for Research On Cancer classifies red meat as probably carcinogenic, and processed meat as carcinogenic.

You can reduce the development of HCAs and PAHs by varying your cooking methods. Some tips include:

- Flipping your meat over more frequently to avoid charring

- Avoid exposing the meat to an open flame or hot metal surface

- Using a microwave or other low-heat cooking methods to preheat meat to reduce cooking time in a pan or on a grill

- Removing charred portions of your meat before eating

Processed Meat

Meats processed by salting, curing, or smoking are associated with health risks, including:

- Increased risk of type 2 diabetes

- Cardiovascular disease

- Cancer (particularly colorectal)

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

You can mitigate much of the cancer risk by consuming fibers and plant-based antioxidants, such as in vegetables, culinary herbs, and fruits. However, it is best to make sure your diet is high in fresh and minimally processed meat cooked at lower heat.

Elevated Creatinine

We all have creatinine in our blood, and it’s a byproduct of muscle breakdown and protein metabolism. High protein diets increase your creatinine because you are metabolizing more amino acids. Having high creatinine is not harmful in the context of a high-protein diet.

If your creatinine levels are high and your diet is not high in protein, you should see your doctor and ask about your kidney function.

The Takeaway

Protein is essential for your entire body, and even more important for ensuring you get adequate amounts of all nine essential amino acids. Throw away the old RDA recommendations for protein intake and focus on the new ones.

How much you need depends on many factors, including your activity level, age, gender, and weight goals. While it might be easy to reach your protein goal in grams, if you rely on a heavily plant-based diet, ensure you get the complete amino acid package daily.

Also, consider adding the following to achieve your daily protein intake and maximize amino acid assimilation.

- Protein Breakthrough is a delicious plant-based complete protein blend. It’s also high in fiber and plant antioxidants.

- MassZymes is a high-protease full-spectrum plant-based digestive enzyme blend that can help maximize protein digestion.

- HCL Breakthrough is a blend of betaine HCL and digestive enzymes that work best in the acidic conditions in the stomach. By maximizing stomach acidity and digestion in the stomach, you maximize protein digestion and absorption.

References

- Carbone JW, Pasiakos SM. Dietary protein and muscle mass: Translating science to application and health benefit. Nutrients. 2019;11(5):1136. doi:10.3390/nu11051136

- Harrop JS, Rodriguez DJ, Benzel EC. Nutritional care of the spinal cord injured patient. In: Spine Surgery. Elsevier; 2005:1873-1886.

- Millward DJ. Identifying recommended dietary allowances for protein and amino acids: a critique of the 2007 WHO/FAO/UNU report. Br J Nutr. 2012;108 Suppl 2(S2):S3-21. doi:10.1017/S0007114512002450

- Wolfe RR, Cifelli AM, Kostas G, Kim IY. Optimizing protein intake in adults: Interpretation and application of the recommended dietary allowance compared with the acceptable macronutrient distribution range. Adv Nutr. 2017;8(2):266-275. doi:10.3945/an.116.013821

- Elango R, Ball RO, Pencharz PB. Recent advances in determining protein and amino acid requirements in humans. Br J Nutr. 2012;108 Suppl 2(S2):S22-30. doi:10.1017/S0007114512002504

- Hayamizu K, Aoki Y, Izumo N, Nakano M. Estimation of inter-individual variability of protein requirement by indicator amino acid oxidation method. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2021;68(1):32-36. doi:10.3164/jcbn.20-79

- Jäger R, Kerksick CM, Campbell BI, et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: protein and exercise. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2017;14(1). doi:10.1186/s12970-017-0177-8

- Antonio J, Ellerbroek A, Silver T, Vargas L, Peacock C. The effects of a high protein diet on indices of health and body composition–a crossover trial in resistance-trained men. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2016;13(1):3. doi:10.1186/s12970-016-0114-2

- Antonio J, Peacock CA, Ellerbroek A, Fromhoff B, Silver T. The effects of consuming a high protein diet (4.4 g/kg/d) on body composition in resistance-trained individuals. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2014;11(1):19. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-11-19

- Antonio J, Ellerbroek A, Silver T, et al. A high protein diet (3.4 g/kg/d) combined with a heavy resistance training program improves body composition in healthy trained men and women–a follow-up investigation. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2015;12(1):39. doi:10.1186/s12970-015-0100-0

- Hector AJ, Phillips SM. Protein recommendations for weight loss in elite athletes: A focus on body composition and performance. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2018;28(2):170-177. doi:10.1123/ijsnem.2017-0273

- Witard OC, Garthe I, Phillips SM. Dietary protein for training adaptation and body composition manipulation in track and field athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2019;29(2):165-174. doi:10.1123/ijsnem.2018-0267

- Malowany JM, West DWD, Williamson E, et al. Protein to maximize whole-body anabolism in resistance-trained females after exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(4):798-804. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000001832

- Wooding DJ, Packer JE, Kato H, et al. Increased protein requirements in female athletes after variable-intensity exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49(11):2297-2304. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000001366

- Kriengsinyos W, Wykes LJ, Goonewardene LA, Ball RO, Pencharz PB. Phase of menstrual cycle affects lysine requirement in healthy women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287(3):E489-96. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00262.2003

- Wohlgemuth KJ, Arieta LR, Brewer GJ, Hoselton AL, Gould LM, Smith-Ryan AE. Sex differences and considerations for female specific nutritional strategies: a narrative review. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2021;18(1):27. doi:10.1186/s12970-021-00422-8

- Imdad A, Bhutta ZA. Maternal nutrition and birth outcomes: effect of balanced protein-energy supplementation: Maternal nutrition and birth outcomes. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26 Suppl 1:178-190. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2012.01308.x

- Stephens TV, Payne M, Ball RO, Pencharz PB, Elango R. Protein requirements of healthy pregnant women during early and late gestation are higher than current recommendations. J Nutr. 2015;145(1):73-78. doi:10.3945/jn.114.198622

- Motil KJ, Davis TA, Montandon CM, Wong WW, Klein PD, Reeds PJ. Whole-body protein turnover in the fed state is reduced in response to dietary protein restriction in lactating women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64(1):32-39. doi:10.1093/ajcn/64.1.32

- Motil KJ, Montandon CM, Thotathuchery M, Garza C. Dietary protein and nitrogen balance in lactating and nonlactating women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;51(3):378-384. doi:10.1093/ajcn/51.3.378

- Landi F, Calvani R, Cesari M, et al. Sarcopenia as the biological substrate of physical frailty. Clin Geriatr Med. 2015;31(3):367-374. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2015.04.005

- Burd NA, Gorissen SH, van Loon LJC. Anabolic resistance of muscle protein synthesis with aging. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2013;41(3):169-173. doi:10.1097/JES.0b013e318292f3d5

- Nabuco H, Tomeleri C, Sugihara Junior P, et al. Effects of whey protein supplementation pre- or post-resistance training on muscle mass, muscular strength, and functional capacity in pre-conditioned older women: A randomized clinical trial. Nutrients. 2018;10(5):563. doi:10.3390/nu10050563

- Mitchell CJ, Milan AM, Mitchell SM, et al. The effects of dietary protein intake on appendicular lean mass and muscle function in elderly men: a 10-wk randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(6):1375-1383. doi:10.3945/ajcn.117.160325

- Groenendijk I, den Boeft L, van Loon LJC, de Groot LCPGM. High versus low dietary protein intake and bone health in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2019;17:1101-1112. doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2019.07.005

- Panula J, Pihlajamäki H, Mattila VM, et al. Mortality and cause of death in hip fracture patients aged 65 or older: a population-based study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12(1):105. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-12-105

- Elango R, Humayun MA, Ball RO, Pencharz PB. Protein requirement of healthy school-age children determined by the indicator amino acid oxidation method. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(6):1545-1552. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.012815

- Young VR, Pellett PL. Plant proteins in relation to human protein and amino acid nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59(5 Suppl):1203S-1212S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/59.5.1203S

- Fotschki B, Juśkiewicz J, Jurgoński A, et al. Protein-rich flours from quinoa and buckwheat favourably affect the growth parameters, intestinal microbial activity and plasma lipid profile of rats. Nutrients. 2020;12(9):2781. doi:10.3390/nu12092781

- Hertzler SR, Lieblein-Boff JC, Weiler M, Allgeier C. Plant proteins: Assessing their nutritional quality and effects on health and physical function. Nutrients. 2020;12(12):3704. doi:10.3390/nu12123704

- Anwar D, El-Chaghaby G. Nutritional quality, amino acid profiles, protein digestibility corrected amino acid scores and antioxidant properties of fried tofu and seitan. Food and Environment Safety Journal. 2019;18(3).

- Masten Rutar J, Jagodic Hudobivnik M, Nečemer M, Vogel Mikuš K, Arčon I, Ogrinc N. Nutritional quality and safety of the Spirulina dietary supplements sold on the Slovenian market. Foods. 2022;11(6):849. doi:10.3390/foods11060849

- Finnigan TJA, Wall BT, Wilde PJ, Stephens FB, Taylor SL, Freedman MR. Mycoprotein: The future of nutritious nonmeat protein, a symposium review. Curr Dev Nutr. 2019;3(6):nzz021. doi:10.1093/cdn/nzz021

- Gilani S, Tomé D, Moughan PJ, Burlingame B, Rutherfurd SM. Report of a Sub-Committee of the 2011 FAO Consultation on “Protein Quality Evaluation in Human Nutrition” on: The assessment of amino acid digestibility in foods for humans and including a collation of published ileal amino acid digestibility data for human foods. Fao.org. Accessed September 6, 2022. https://www.fao.org/ag/humannutrition/36216-04a2f02ec02eafd4f457dd2c9851b4c45.pdf

- Sarwar Gilani G, Wu Xiao C, Cockell KA. Impact of antinutritional factors in food proteins on the digestibility of protein and the bioavailability of amino acids and on protein quality. Br J Nutr. 2012;108 Suppl 2(S2):S315-32. doi:10.1017/S0007114512002371

- Ciuris C, Lynch HM, Wharton C, Johnston CS. A comparison of dietary protein digestibility, based on DIAAS scoring, in vegetarian and non-vegetarian athletes. Nutrients. 2019;11(12):3016. doi:10.3390/nu11123016

- Churchward-Venne TA, Breen L, Di Donato DM, et al. Leucine supplementation of a low-protein mixed macronutrient beverage enhances myofibrillar protein synthesis in young men: a double-blind, randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(2):276-286. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.068775

- Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kramer HM, Fouque D. High-protein diet is bad for kidney health: unleashing the taboo. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35(1):1-4. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfz216

- Helal I, Fick-Brosnahan GM, Reed-Gitomer B, Schrier RW. Glomerular hyperfiltration: definitions, mechanisms and clinical implications. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8(5):293-300. doi:10.1038/nrneph.2012.19

- Zhao J, Zhang X, Liu H, Brown MA, Qiao S. Dietary protein and gut Microbiota composition and function. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2018;20(2):145-154. doi:10.2174/1389203719666180514145437

- Cross AJ, Sinha R. Meat-related mutagens/carcinogens in the etiology of colorectal cancer. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2004;44(1):44-55. doi:10.1002/em.20030

- Lyon F. IARC Monographs evaluate consumption of red meat and processed meat. Who.int. Published 2015. Accessed September 6, 2022. https://www.iarc.who.int/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/pr240_E.pdf

- Knize MG, Felton JS. Formation and human risk of carcinogenic heterocyclic amines formed from natural precursors in meat. Nutr Rev. 2005;63(5):158-165. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2005.tb00133.x

- Mozaffarian D. Dietary and policy priorities for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity: A comprehensive review: A comprehensive review. Circulation. 2016;133(2):187-225. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018585

- Abete I, Romaguera D, Vieira AR, Lopez de Munain A, Norat T. Association between total, processed, red and white meat consumption and all-cause, CVD and IHD mortality: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Br J Nutr. 2014;112(5):762-775. doi:10.1017/S000711451400124X

- Benarba B. Red and processed meat and risk of colorectal cancer: an update. EXCLI J. 2018;17:792-797. doi:10.17179/excli2018-1554

- Masrul M, Nindrea RD. Dietary fibre protective against colorectal cancer patients in Asia: A meta-analysis. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7(10):1723-1727. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2019.265

- Ding S, Xu S, Fang J, Jiang H. The protective effect of polyphenols for colorectal cancer. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1407. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.01407