What Causes High Cholesterol and Does It Really Cause Heart Disease?

What Causes High Cholesterol and Does It Really Cause Heart Disease?

Why Cholesterol Gets A Bad Rep

Many people, including medical professionals, think cholesterol causes heart disease, even though the notion has been debunked.

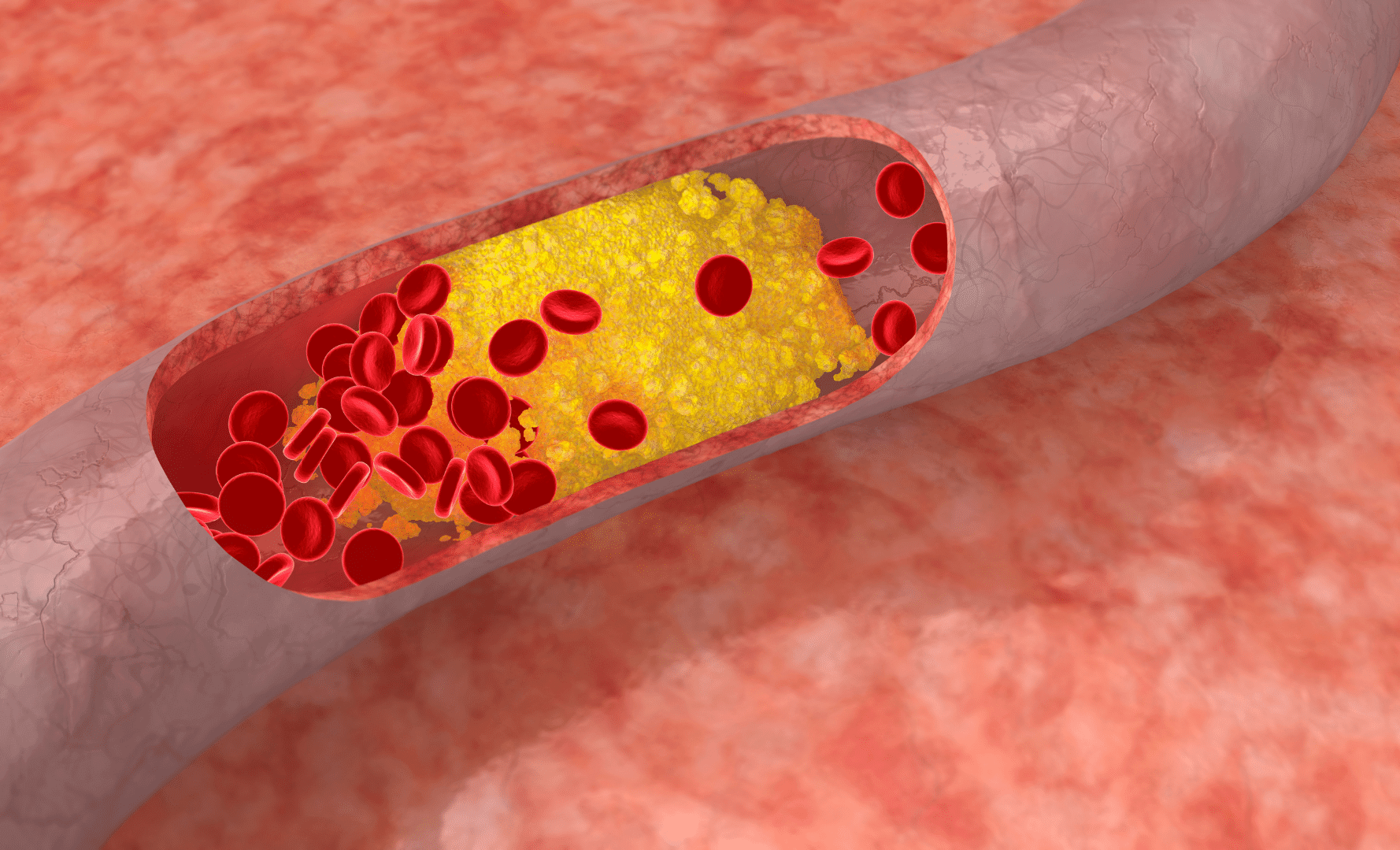

Cholesterol is a fat-like waxy substance found in your blood. When anatomists study people with clogged arteries or buildup in the blood vessels, they find that the buildups contain cholesterol. We call this build-up atherosclerosis.

The idea that eating too much cholesterol can cause cardiovascular disease (CVD) began with a study in 1971. When they fed rabbits cholesterol, their cholesterol shot up 17 times and the rabbits started to develop heart disease. However, humans are not rabbits. We’re omnivores not herbivores.]

Many studies also found high cholesterol in people with higher risk of CVD. The researchers then proposed that the high cholesterol levels came from consuming too much cholesterol through the diet. Despite follow-up research to the contrary, the scientific community and public accepted this idea for decades.

In 1988, eggs (which are high in cholesterol) were villainized by a study that connected mortality and heart disease with egg consumption in women. Multiple follow-up studies debunked the idea that eggs contribute to high cholesterol, but yet again, the idea persisted.

So, why all of the confusion? The thing about high-cholesterol foods is that they also tend to be high in animal-based saturated fat– except for eggs and shrimp. Researchers found an accurate correlation, but attacked the wrong culprit.

Unlike the inconsistent studies surrounding the link between cholesterol in food and heart disease, the connection between saturated fat and heart disease is well-documented. A literature review by the American Heart Association established that CVD risk decreases when polyunsaturated or monounsaturated fats replace saturated fats.

Why Cholesterol And LDL-C Don’t Cause Heart Disease

The bottom line is that your total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol are probably not what’s causing heart disease. It’s more complicated than that.

A literature review conducted a deep dive into CVD and LDL cholesterol studies. The researchers found that previous studies linking cholesterol to CVD contained errors. Let’s break down some of the big ones.

If it’s true that total cholesterol levels cause heart disease, then people with high total cholesterol should have higher rates of heart disease. However, studies show no difference in heart disease rates regardless of cholesterol levels. Additionally, when patients took cholesterol-lowering medication, total cholesterol declined. However, the medication and lower cholesterol levels did not change the rate of heart disease.

This same review found that many studies disprove the relationship between LDL and heart disease. They could not establish any link between LDL cholesterol and atherosclerosis, the most common cause of CVD.

Multiple studies found that those with heart disease actually have low LDL levels. A massive study of almost 140,000 American patients admitted to the hospital with a heart attack had low LDL levels. The review also highlighted a study of elderly Japanese people showing that those with high LDL levels lived longer than those with lower LDL levels. This supports the idea that high LDL may be healthy, at least in the elderly.

Beyond LDL, many other factors influence your risk of heart disease. They include:

- High blood pressure

- Diabetes

- Smoking

- Obesity

- Inactivity

- Unhealthy diet

- Inflammation

- Unhealthy calcium balance and vitamin K levels

Essential Functions Of Cholesterol

Cholesterol is essential for your overall health and well-being. It is in your blood and every cell in your body. Its primary role is to maintain the cell in perfect condition and also allow your cells to change shape and move. It is so critical to your body that your liver produces between 70-80% of the cholesterol you need, and just 20-30% comes from your diet.

You also need cholesterol for many other essential substances in your body. Without cholesterol, you would not be able to produce adequate amounts of:

- Steroid hormones like testosterone, estrogen, and cortisol

- Bile acids in the liver

- Vitamin D

How Dietary Cholesterol Affects Cholesterol Levels

Remember that your liver manages most of your cholesterol needs. Your body knows what it needs to maintain homeostasis and will make the necessary adjustments based on how much cholesterol you get from your diet.

A meta-analysis explored the relationship between dietary cholesterol and blood cholesterol levels. Overall, studies failed to demonstrate a correlation between the two. Researchers believe studies fail to consider what happens after you eat cholesterol. It doesn’t go directly into your blood.

When you eat cholesterol, it travels into your intestines, where most of it enters the cell in your intestinal lining. The rest flows back to the intestines and leaves your body along with your stool. The cholesterol that enters your cells gets packed up along with triglycerides (fat) into chylomicrons and goes into circulation.

The chylomicrons then lose most triglycerides and head to the liver, removing them from circulation. When cholesterol-loaded chylomicrons are present in the liver, it inhibits the liver from producing cholesterol. Therefore, the more dietary cholesterol you consume, the less your liver will produce.

Researchers are so convinced that consuming cholesterol through your diet does not raise cholesterol levels that the most recent Dietary Guidelines for Americans removed the upper limit for cholesterol consumption. They do, however, still maintain that you should keep your consumption low.

What you do need to look out for is eating high-cholesterol foods that are also high in saturated or trans fats. They are more likely to increase your blood cholesterol levels.

A study of 84 men examined the effects of cholesterol and saturated fat on LDL levels. Subjects consumed 600 mg of cholesterol with either high saturated/low polyunsaturated or high polyunsaturated/low saturated fat. Those subjects who consumed the high saturated fat and cholesterol experienced a much more significant increase in LDL than those who consumed the polyunsaturated fat.

Now that you know that dietary cholesterol may not be an issue, let’s look at various types of blood lipid measures and how they relate to your health according to the latest evidence. Nowadays, you can get more advanced tests based on nuclear magnetic resonance technologies, which can measure particle size. These tests are more illuminating than either HDL and LDL alone.

Different Types Of Cholesterol On The Bloodwork And How They Associate With Health Risks

When you get your cholesterol levels tested, there’s much more than the well-known HDL and LDL that tell you about your health, which can be confusing. Let’s dig into each of them one by one.

High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL)

HDL refers to high-density lipoprotein and is traditionally considered the “good” cholesterol. It gets its shiny reputation from its role in escorting cholesterol out of the body to be excreted. The normal range for HDL is:

- Between 40 to 60 mg/dL (milligrams per deciliter) or 1.04 to 1.55 mmol/L (millimoles per liter) for men

- Between 50 to 60 mg/dL (1.3 to 1.55 mmol/L) for women

Studies are mixed as to whether you’re at risk for certain conditions when you have too much HDL. Regardless, HDL levels outside of the normal range may put you at more risk for:

- Age-related macular degeneration, which causes vision loss and blindness in the elderly population

- Cognitive decline and dementia

- Diabetes – researchers have agreed that low HDL levels put you at greater risk.

Maintaining healthy HDL cholesterol levels helps support your innate and adaptive immune systems and decreases your risk of infection.

Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL)

Low-density lipoprotein (LDL), traditionally called the “bad” cholesterol, makes up most of the cholesterol in your body. It moves cholesterol around the body to repair cells. The ideal LDL level on a blood test is below 100 mg/dL (2.59 mmol/L).

When doctors look at your LDL levels, they see how much LDL is in your system. If your levels are high, it suggests you have a lot of cholesterol carried around the body. The cholesterol may then invade the walls of your blood vessels and cause inflammation. When this happens, plaque can form in your arteries, putting you at higher risk for developing atherosclerosis and, eventually, heart attack or stroke.

LDL particles don’t all come in the same size and carry varying amounts of cholesterol. Because there are different types of LDL particles, the LDL test doesn’t tell you the contents of your LDL. Testing for the subtype can tell you even more about your level of risk and also may explain why there is a discrepancy in health outcomes for those with the same level of LDL.

Small Dense Low-Density Lipoprotein (sdLDL)

sdLDL is a small and dense LDL type – meaning the particles are small and carry a lot of cholesterol. sdLDL tends to stay around in your blood longer than other subclasses of LDL. And it promotes fatty plaques in the arteries more than any other subclass, making it a strong biomarker, or indicator, of heart disease risk.

In addition to its association with heart disease, research links high levels of sdLDL to:

- Obesity

- Inflammation

- Thrombosis – occurs when blood clots form in veins or arteries, increasing your risk of stroke or heart attack

- Metabolic syndrome – characterized by high blood sugar, high blood pressure, and a large waist circumference

- Increased risk of type 2 diabetes

A study of 1,065 males explored the relationship between sdLDL levels and metabolic syndrome. Subjects did not experience obesity, inflammation, or diabetes, commonly linked to metabolic syndrome. But still, those with higher concentrations of sdLDL were more likely to have metabolic syndrome.

Very Low Density Lipoprotein (vLDL)

Another subclass of LDL is vLDL – very low-density lipoprotein. These are lighter and fluffier than sdLDL. Its primary role is to carry triglycerides, or blood fats, throughout the body. These triglycerides come from your food, and your cells use them as energy.

There is no direct way to measure your vLDL levels. Labs estimate your levels at around one-fifth of your triglyceride levels. Normal range of vLDL is between 2 and 30 mg/dL (0.05 to 0.78 mmol/L).

While vLDL plays a critical role (at high levels), it puts you at risk for atherosclerosis. They contain both cholesterol and triglycerides and are small enough to enter your cell walls. Once inside, they get trapped, accumulate, and cause low-grade inflammation.

In a cohort study of 8,057 subjects with cardiovascular disease, researchers wanted to know whether high levels of vLDL were a risk factor for major adverse cardiovascular events. Subjects with high levels of vLDL were more likely to experience major adverse limb events such as:

- Untreated blocked arteries in their arms and legs

- Major amputation

They were also more likely to experience a heart attack, but not as likely to experience stroke or death.

Triglycerides

Triglycerides are the most common fat found in your body. They are essential for your body to give you energy. And as long as you stay within a normal fasting range of 150 mg/dL (3.89 mmol/L), you’re in great shape. The problems arise when those levels get too high:

- Moderately high – 150 to 199 mg/dL (3.89 to 5.15 mmol/L)

- High – 200 to 499 mg/dL (5.18 to 12.92 mmol/L)

- Very high – 500 mg/dL (12.95 mmol/L) and above

Clinically speaking, having high triglycerides is relatively common, affecting about 10% of adults.

When triglycerides break down, there are little bits left over called remnants. Your body has no use for these remnants, so they stick around, triggering inflammation in your arteries and leading to plaque buildup.

High levels of triglycerides increase your risk of heart attack or stroke. At very high levels, triglycerides frequently cause inflammation of the pancreas.

Lipoprotein (a) Or Lp(a)

Lipoprotein (a), generally referred to as “L-P-little-A,” is similar to LDL cholesterol, but stickier because attached to it is apolipoprotein (a). Being sticky isn’t a good thing when it comes to trying to achieve the goal of clear arteries.

Apolipoprotein (a) looks to your body like something called a plasminogen that protects your blood from clotting. Instead, it competes with your plasminogen making it harder for your body to break up clots.

Because Lp(a) is so sticky, it can gradually build up in your arteries and narrow them, not allowing blood to pass throughout the body. It affects not only your heart, but also other parts of your body, such as your:

- Brain

- Kidneys

- Lungs

- Legs

Lp(a) is the one cardiovascular blood marker that is determined entirely by your genetics, not your lifestyle. It also does not differ much between different sexes or ages. While Lp(a) appears in all races and ethnicities, black people are more likely to have high Lp(a) levels. Your levels are considered high when greater than 50 mg/dL (1.3 mmol/L).

A meta-analysis exploring the relationship between Lp(a) and health risk factors determined that high Lp(a) is:

- A risk factor for CVD, even without any other risk factors present

- Common in chronic kidney disease.

- A factor in the cause of:

- Coronary artery disease

- Heart attacks

- Stroke

- Peripheral artery disease

- Heart disease

Knowing your family history is a great place to start to know whether or not high Lp(a) may be an issue for you. It’s also wise to ask your doctor for an Lp(a) test so you know your risk.

Apolipoprotein B (ApoB)

Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) is the main protein in every lipoprotein that promotes plaque and clogs your arteries. ApoB works by attaching to receptors on your cells, allowing the lipoproteins it carries into your cells. The lipoproteins then break down and release cholesterol. The cholesterol is either used as energy, stored for later use, or removed.

Because ApoB gives you a more exact count of the number of particles in your blood that could contribute to CVD, researchers consider it a more accurate measure of cardiovascular risk. Your LDL levels alone don’t give you such detail. Normal ApoB levels are around 90 mg/DL (2.33 mmol/L) or less.

A recent meta-analysis explored the relationship between high ApoB levels and health risks. Overall, higher levels of ApoB:

- Shorten lifespan

- Increase the risk of heart disease and stroke

- Increase the risk of type 2 diabetes

High levels of ApoB and high levels of LDL may also indicate an underactive thyroid.

While your overall cholesterol levels are important, they only tell one part of your story. Looking into the different factors of your blood lipids can give you a more in-depth understanding of any health risks.

Takeaway

Cholesterol may have a bad reputation when it comes to your heart health, but it’s not entirely accurate. While having high amounts of certain types of cholesterol may make you more likely to experience cardiovascular disease, it is not as simple as looking at your total cholesterol or HDL and LDL levels. Here are some things to keep in mind:

- Eating a diet high in cholesterol alone is unlikely to increase your blood cholesterol levels

- Saturated fats and trans fats in foods that contain cholesterol are more dangerous than just cholesterol for your heart health

- Be aware of genetic factors such as high ApoB and Lp(a) levels.

- Refer back to this article when you get your blood test results to understand better what doctors are looking for

References

- Kolodgie FD, Katocs AS Jr, Largis EE, et al. Hypercholesterolemia in the rabbit induced by feeding graded amounts of low-level cholesterol. Methodological considerations regarding individual variability in response to dietary cholesterol and development of lesion type: Methodological considerations regarding individual variability in response to dietary cholesterol and development of lesion type. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16(12):1454-1464. doi:10.1161/01.atv.16.12.1454

- Kannel WB. Serum cholesterol, lipoproteins, and the risk of coronary heart disease: The Framingham study. Ann Intern Med. 1971;74(1):1. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-74-1-1

- Soliman G. Dietary cholesterol and the lack of evidence in cardiovascular disease. Nutrients. 2018;10(6):780. doi:10.3390/nu10060780

- Snowdon DA. Animal product consumption and mortality because of all causes combined, coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and cancer in Seventh-day Adventists. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;48(3):739-748. doi:10.1093/ajcn/48.3.739

- Sacks FM, Lichtenstein AH, Wu JHY, et al. Dietary fats and cardiovascular disease: A presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136(3):e1-e23. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000510

- Ravnskov U, de Lorgeril M, Diamond DM, et al. LDL-C Does Not Cause Cardiovascular Disease: a comprehensive review of current literature. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2018;11(10):959-970. doi:10.1080/17512433.2018.1519391

- Heart disease and stroke. Cdc.gov. Published September 8, 2022. Accessed March 4, 2023. http://cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/factsheets/heart-disease-stroke.htm

- Hariri E, Kassis N, Iskandar JP, et al. Vitamin K2-a neglected player in cardiovascular health: a narrative review. Open Heart. 2021;8(2):e001715. doi:10.1136/openhrt-2021-001715

- Zampelas A, Magriplis E. New insights into cholesterol functions: A friend or an enemy? Nutrients. 2019;11(7):1645. doi:10.3390/nu11071645

- Moon JY, Choi MH, Kim J. Metabolic profiling of cholesterol and sex steroid hormones to monitor urological diseases. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2016;23(10):R455-67. doi:10.1530/ERC-16-0285

- Li T, Chiang JYL. Regulation of bile acid and cholesterol metabolism by PPARs. PPAR Res. 2009;2009:501739. doi:10.1155/2009/501739

- Surdu AM, Pînzariu O, Ciobanu DM, et al. Vitamin D and its role in the lipid metabolism and the development of atherosclerosis. Biomedicines. 2021;9(2):172. doi:10.3390/biomedicines9020172

- Fernandez ML, Murillo AG. Is there a correlation between dietary and blood cholesterol? Evidence from epidemiological data and clinical interventions. Nutrients. 2022;14(10). doi:10.3390/nu14102168

- This publication may be viewed and downloaded from the internet at. Dietaryguidelines.gov. Accessed March 4, 2023. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf

- Fielding CJ, Havel RJ, Todd KM, et al. Effects of dietary cholesterol and fat saturation on plasma lipoproteins in an ethnically diverse population of healthy young men. J Clin Invest. 1995;95(2):611-618. doi:10.1172/JCI117705

- CDC. About cholesterol. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published December 14, 2022. Accessed March 4, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cholesterol/about.htm

- Kjeldsen EW, Nordestgaard LT, Frikke-Schmidt R. HDL cholesterol and non-cardiovascular disease: A narrative review. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(9). doi:10.3390/ijms22094547

- Pirahanchi Y, Sinawe H, Dimri M. Biochemistry, LDL Cholesterol. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Nomura SO, Karger AB, Garg P, et al. Small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol compared to other lipoprotein biomarkers for predicting coronary heart disease among individuals with normal fasting glucose: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2023;13(100436):100436. doi:10.1016/j.ajpc.2022.100436

- Ivanova EA, Myasoedova VA, Melnichenko AA, Grechko AV, Orekhov AN. Small dense low-density lipoprotein as biomarker for atherosclerotic diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:1273042. doi:10.1155/2017/1273042

- Kulanuwat S, Tungtrongchitr R, Billington D, Davies IG. Prevalence of plasma small dense LDL is increased in obesity in a Thai population. Lipids Health Dis. 2015;14(1):30. doi:10.1186/s12944-015-0034-1

- Fan J, Liu Y, Yin S, et al. Small dense LDL cholesterol is associated with metabolic syndrome traits independently of obesity and inflammation. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2019;16(1):7. doi:10.1186/s12986-019-0334-y

- Hsu SHJ, Jang MH, Torng PL, Su TC. Positive association between small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration and biomarkers of inflammation, thrombosis, and prediabetes in non-diabetic adults. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2019;26(7):624-635. doi:10.5551/jat.43968

- Lee Y, Siddiqui WJ. Cholesterol Levels. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Heidemann BE, Koopal C, Bots ML, Asselbergs FW, Westerink J, Visseren FLJ. The relation between VLDL-cholesterol and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with manifest cardiovascular disease. Int J Cardiol. 2021;322:251-257. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.08.030

- Laufs U, Parhofer KG, Ginsberg HN, Hegele RA. Clinical review on triglycerides. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(1):99-109c. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz785

- Edelberg JM, Pizzo SV. Lipoprotein (a) in the regulation of fibrinolysis. J Atheroscler Thromb. 1995;2(Supplement1):S5-S7. doi:10.5551/jat1994.2.supplement1_s5

- Patel AP, Wang (汪敏先) M, Pirruccello JP, et al. Lp(a) (lipoprotein[a]) concentrations and incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: New insights from a large national Biobank: New insights from a large national Biobank. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41(1):465-474. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.315291

- Lipoprotein (a). Cdc.gov. Published November 30, 2022. Accessed March 4, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/genomics/disease/lipoprotein_a.htm

- Enas EA, Varkey B, Dharmarajan TS, Pare G, Bahl VK. Lipoprotein(a): An independent, genetic, and causal factor for cardiovascular disease and acute myocardial infarction. Indian Heart J. 2019;71(2):99-112. doi:10.1016/j.ihj.2019.03.004

- Behbodikhah J, Ahmed S, Elyasi A, et al. Apolipoprotein B and cardiovascular disease: Biomarker and potential therapeutic target. Metabolites. 2021;11(10):690. doi:10.3390/metabo11100690

- Sadovsky R. Using apolipoprotein B levels to assess cardiac risk. afp. 2003;67(6):1386-1386. Accessed March 4, 2023. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2003/0315/p1386.html

- Richardson TG, Wang Q, Sanderson E, et al. Effects of apolipoprotein B on lifespan and risks of major diseases including type 2 diabetes: a mendelian randomisation analysis using outcomes in first-degree relatives. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2(6):e317-e326. doi:10.1016/S2666-7568(21)00086-6

- Mugii S, Hanada H, Okubo M, et al. Thyroid function influences serum apolipoprotein B-48 levels in patients with thyroid disease. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2012;19(10):890-896. doi:10.5551/jat.12757